Design and evaluation of controller-based raycasting methods for secure and efficient text entry in virtual reality

Overview

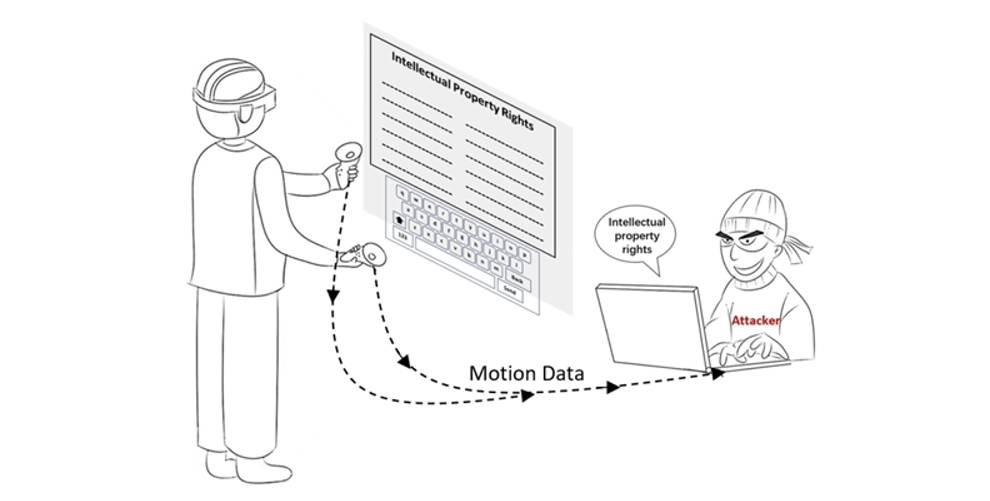

This work focuses on improving text input security in virtual reality (VR) environments, where inconspicuous motion and location sensors can expose user inputs during typing. To address this challenge, we designed five innovative keyboard layouts for paragraph and password input that enhance input privacy while maintaining high usability and typing performance.

This project has been published in two research papers:

- Analysis and Design of Efficient Authentication Techniques for Password Entry with the Qwerty Keyboard for VR Environments

- Design and Evaluation of Controller-based Raycasting Methods for Secure and Efficient Text Entry in Virtual Reality

My Contribution: I was responsible for all technical implementations and part of the idea generation.

Layout Design

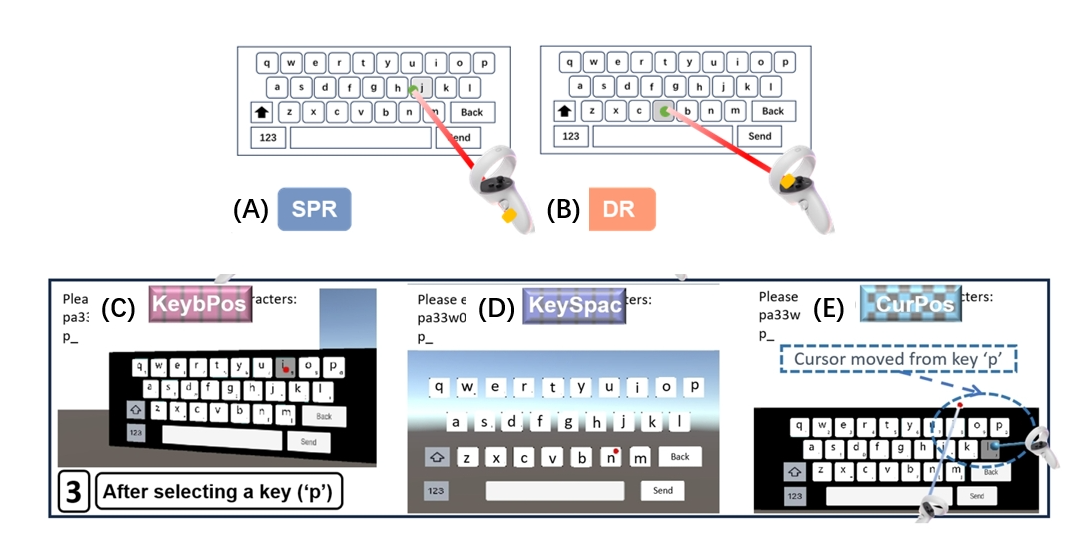

We have designed five innovative keyboard layouts (two for paragraph and three for password) that aim to counter shoulder-surfing attacks while maintaining high typing performance. Each layout introduces strategic variations to ensure security without compromising user efficiency, as shown in figure:

For paragraph protection:

(A) Introducing Variability in Start Point of the Ray (SPR)

The starting point of the ray is randomly shifted forward or backward after each confirmation of a selection. While the starting position changes, the ray’s direction remains constant, ensuring the pointing position on the virtual keyboard is unaffected.

(B) Introducing Variability in Direction of the Ray (DR)

The direction of the ray is adjusted randomly after each confirmation of selection, ensuring variations in the angles and introducing unpredictability into the selection process.

Since it’s for long text entry, to balance security and performance, two optimizations are proposed:

- Random Interval Frequency: Instead of altering the ray after every keystroke, changes are made within a random range of 4 to 12 keystrokes, improving typing performance while maintaining privacy.

- Combining SPR and DR: By combining intermittent changes in the ray’s starting position (SPR) and direction (DR), variability is introduced both spatially and directionally. This approach increases unpredictability and enhances security.

These optimizations strike a balance between security (input privacy) and typing performance.

For password protection:

(C) Altering Entire Keyboard Position (KeybPos) The keyboard’s position is randomly shifted (up, down, left, or right) after each key selection. This strategy disrupts the selection-making tool’s displacement while maintaining the integrity of the QWERTY layout, ensuring user familiarity.

(D) Altering Key Spacing (KeySpace) The spacing between keys is adjusted after each key selection, introducing variations in the required displacement to select a key. This method reduces eye strain, maintains familiarity with key size, and helps users develop strong spatial awareness of key positions.

(E) Altering Cursor Position (CurPos) Instead of shifting the entire keyboard, this strategy moves the cursor’s position on the keyboard after each key selection. The movement corresponds to a shift of the keyboard selection tool, preserving consistent visual positioning and reducing disorientation.

Effectiveness Validation

In order to evaluate the protecting performance of four password protection strategies, we implemented a password prediction method. By comparing the prediction accuracy of the standard keyboard with that of the other four strategies, we aimed to determine the relative robustness of each approach. The detailed implementation of this method, including the data analysis and reconstruction processes, is shown below:

1. 3D Cursor Position Estimation

3D Cursor Position Estimation depends on both the position of the controller (i.e., $(x, y, z)$ coordinates) and the orientation of the controller (attitude angles, including pitch, roll, and yaw). Using mathematical methods, we can compute the controller’s direction in space and determine the exact position of the cursor on the virtual keyboard:

The ray direction is determined by the $(C_z)$ axis of the controller, which is influenced by the pitch angle (Pitch, denoted as $\alpha$) and roll angle (Roll, denoted as $\beta$). The yaw angle (Yaw) has no impact on the laser direction.

We assume that the initial state of the controller is unrotated. In this state, the controller’s direction aligns with the $(G_z)$-axis of the global coordinate system. To calculate the direction of the controller in 3D space after rotation, we use a rotation matrix. The complete rotation matrix $(R)$ is expressed as follows:

\[R =s \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\alpha) & 0 & \sin(\alpha) \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ -\sin(\alpha) & 0 & \cos(\alpha) \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \cos(\beta) & -\sin(\beta) \\ 0 & \sin(\beta) & \cos(\beta) \end{bmatrix}\]Assume the initial position of the controller is $([x, y, z]^T)$. The position of the cursor on the virtual keyboard is essentially the endpoint of a line segment (the perpendicular distance from the controller to the keyboard) rotated in space around the point $([x, y, z]^T)$.

Let the relative distance from the controller to the virtual keyboard along the $(z)$-axis be $(l)$. The true position of the cursor can be calculated as follows:

\[P_c = R \cdot [x, y, z - l]^T\]This formula gives the exact 3D position of the cursor in space based on the controller’s rotation and position.

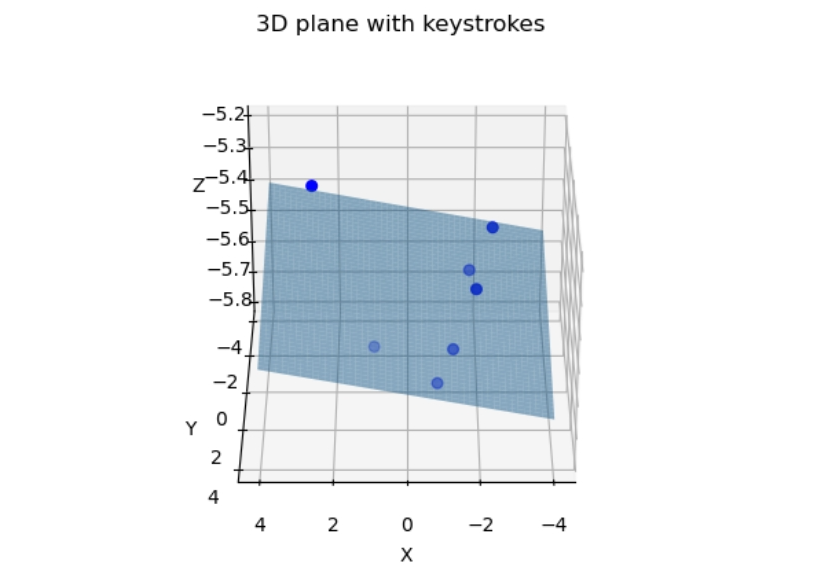

2. Keyboard Plane Estimation In a 3D virtual environment, all keys on the virtual keyboard are assumed to lie on a plane. This plane can be mathematically expressed as:

\[a x + b y + c = z\]where $(a)$, $(b)$, and $(c)$ are the plane parameters, and $(x_i, y_i, z_i)$ represents the 3D coordinates of the $i^{th}$ keystroke, as shown below.

Given multiple detected keystrokes, the plane estimation problem can be formulated as a linear system:

\[\mathbf{A} \mathbf{X} = \mathbf{B}\]Where:

- $\mathbf{A}$ is a matrix consisting of the $x$ and $y$ coordinates of the keystrokes.

- $\mathbf{X}$ is the unknown vector $[a, b, c]^T$.

- $\mathbf{B}$ contains the $z$-coordinates of the keystrokes.

Using Least Square Estimation (LSE), the unknown parameters of the plane can be solved as:

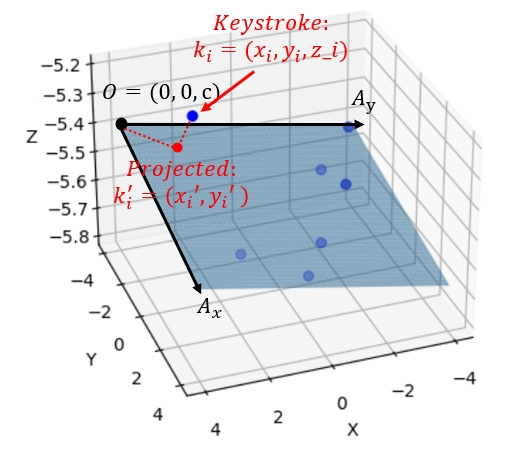

\[\mathbf{X} = [a \ b \ c]^T = (\mathbf{A}^T \mathbf{A})^{-1} \mathbf{A}^T \mathbf{B}\]3. 2D Keystroke Position Projection To obtain the 2D coordinates of the key strokes, we first define the 2D plane:

- Origin $( O = (0, 0, c) )$ is set as the origin of the 2D plane.

- $A_x$ is a vector along the positive $x$-axis direction in the plane, defined as $(1, 0, a + c)$.

Then we calculate the $y$-axis direction according to:

- Define a point $( A_y = (x_y, 1, z_y) )$ on the $y$-axis.

-

Solve the following equations to determine $A_y$:

\[\begin{cases} ax_y + b + c = z_y, \\ A_x \cdot A_y = 0 \end{cases}\]Here, $A_x \cdot A_y = 0$ ensures that $A_y$ is orthogonal to $A_x$.

- Solving these equations gives: \(A_y = \left( -\frac{ab}{a^2 + 1}, 1, \frac{b}{a^2 + 1} + c \right)\)

Finally, we project the 3D keystrokes onto the 2D plane:

- Let $\mathbf{k}_i$ be the vector from $O$ to the $i$-th keystroke’s 3D coordinate $(x_i, y_i, z_i)$.

- The 2D coordinates $(\hat{x}_i, \hat{y}_i)$ of the keystroke in the plane can be obtained as follows: \(x_i' = \frac{\mathbf{k}\_i \cdot A_x}{||A_x||}, \quad y_i' = \frac{\mathbf{k}\_i \cdot A_y}{||A_y||}\)

-

Here:

-

$\mathbf{k}_i \cdot A_x$ and $\mathbf{k}_i \cdot A_y$ represent the dot products of $\mathbf{k}_i$ with $A_x$ and $A_y$, respectively.

-

$||A_x||$ and $||A_y||$ are the magnitudes of $A_x$ and $A_y$.

-

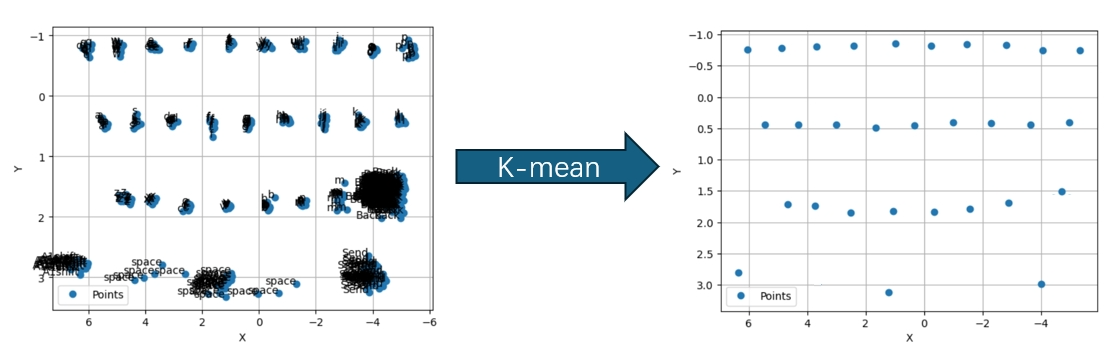

4. Rebuild 2D Keyboard After mapping the key inputs (keystrokes) to the 2D space, we use the K-mean clustering algorithm to obtain the reconstructed keyboard layout, as shown in the figure $(k=30)$.

5. Password Recovery Tree-based Backward Typing Trajectory we uses the “Enter” key as the root node of a tree. By calculating the absolute distance $(D_1)$ between the Send key and the last pressed key, the adversary identifies the 3 closest keys: \((K_1, K_2, K_3)\) The process continues recursively, increasing the depth of the tree, until the tree’s depth matches the password length $(n)$. The total number of candidate passwords is $3^n$.

Path Analysis and Error Calculation We ranks all password candidates based on their relative error $(E_n)$, in ascending order. Candidates with smaller error values are considered more likely. The total error for a password candidate is obtained by summing the accumulated distance and direction similarity:

\[E_n = D_n + Q_n.\](1) Accumulated Distance $(D_n)$ The relative difference of the L2 distances between the reconstructed keyboard and the victim’s trajectory is calculated as:

\[D_n = \sum*{i=1}^{n-1} \sum\_{j=i+1}^n \frac{|D(k_i, k_j) - \hat{D}(k_i, k_j)|}{\hat{D}(k_i, k_j)},\]where:

- $(D(k_i, k_j))$: Distance between keys $(k_i)$ and $(k_j)$ on the reconstructed keyboard.

- $(\hat{D}(k_i, k_j))$: Distance between keys $(k_i)$ and $(k_j)$ in the victim’s typing trajectory.

(2) Direction Similarity $(Q_n)$ The direction similarity is evaluated by calculating the angle difference between key triplets $({k*i, k_j, k_k})$. The angle is defined as:

\[\theta*{ijk} = \arccos{\left(\frac{\vec{k_i k_j} \cdot \vec{k_j k_k}}{|\vec{k_i k_j}||\vec{k_j k_k}|}\right)},\]where:

- $(\vec{k_i k_j})$: Vector from key $(k_i)$ to key $(k_j)$.

- $(\theta_{ijk})$: Angle formed by the key triplet.

The relative angle difference is given by:

\[Q*n = \sum*{i=1}^{n-2} \sum*{j=i+1}^{n-1} \sum*{k=j+1}^n \frac{|\theta*{ijk} - \hat{\theta}*{ijk}|}{\hat{\theta}\_{ijk}}, \quad (i \neq j \neq k),\]where:

- $\theta_{ijk}$: Angle in the reconstructed keyboard.

- $\hat{\theta}_{ijk}$: Angle in the victim’s actual typing path.

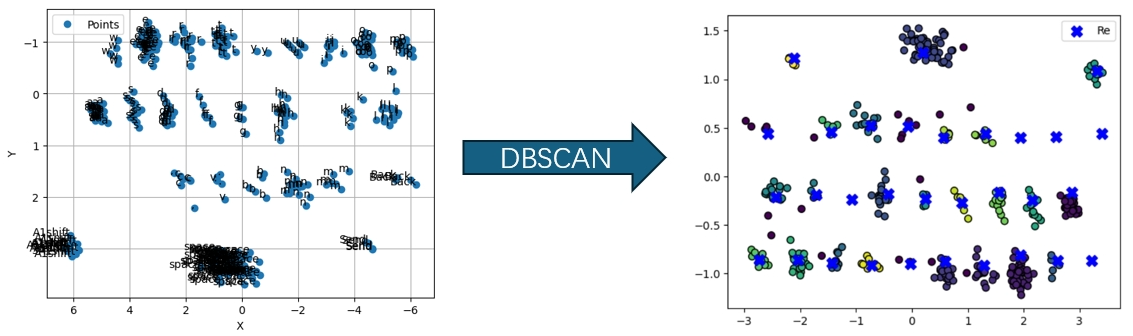

6. Paragraph Recovery We use DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) to cluster the keystroke positions projected into a 2D space. parameters are set as follows:

- the minimum number of points $(MinPts)$

- the maximum neighborhood distance $(\epsilon)$

We adjust the parameters according to the projected 2D keys.

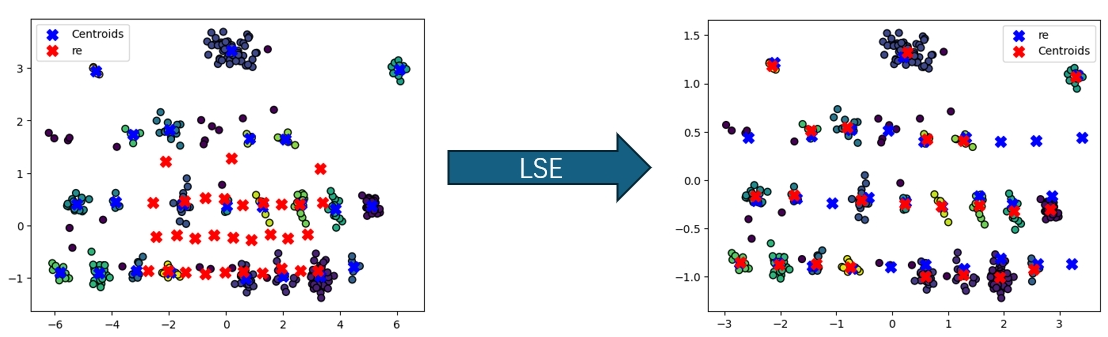

To align the reconstructed keyboard with the victim’s original keyboard, the attacker uses Least Squares Estimation (LSE) for coordinate transformation.

Let the detected cluster centers (blue in figure) be $([x_i, y_i])$ and their corresponding coordinates on the reconstructed keyboard(red in figure) be $([\tilde{x}_i, \tilde{y}_i])$. The linear transformation relationships are as follows:

\[\tilde{x}\_i = a_1 x_i + b_1 y_i + c_1, \tilde{y}\_i = a_2 x_i + b_2 y_i + c_2\]These equations can be expressed in matrix form:

\[\begin{bmatrix} x_0 & y_0 & 1 \\ x_1 & y_1 & 1 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ x_n & y_n & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} a_1 \\ b_1 \\ c_1 \end{bmatrix}= \begin{bmatrix} \hat{x}\_0 \\ \hat{x}\_1 \\ \vdots \\ \hat{x}\_n \end{bmatrix}\quad \text{and} \quad \begin{bmatrix} x_0 & y_0 & 1 \\ x_1 & y_1 & 1 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ x_n & y_n & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} a_2 \\ b_2 \\ c_2 \end{bmatrix}= \begin{bmatrix} \hat{y}\_0 \\ \hat{y}\_1 \\ \vdots \\ \hat{y}\_n \end{bmatrix}\]By solving the above linear systems using LSE, the parameters ( a1, b_1, c_1, a_2, b_2, c_2 ) are obtained to align the two keyboards. The transformed coordinates of the (i)-th key on the aligned keyboard ([x_i^, yi^]) can be calculated as:

\[x*i^* = a*1 x_i + b_1 y_i + c_1, \quad y_i^* = a_2 x_i + b_2 y_i + c_2.\]The alignment accuracy is evaluated by computing the average distance between the aligned coordinates \([x_i^*, y_i^*]\) and the reconstructed coordinates \(([\tilde{x}_i, \tilde{y}_i])\)

After aligning, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) classification algorithm is used to label each key. The value of $(K)$ is set to 1, and the training data consists of the victim’s actual natural language inputs. Each reconstructed keystroke position is matched to the closest key label using KNN. To further improve the accuracy of the reconstructed text, the attacker applies language models for spelling and grammar correction.