Exploration of Foot-based Text Entry Techniques for Virtual Reality Environments

This project has been published in the paper: Exploration of Foot-based Text Entry Techniques for Virtual Reality Environments

Abstract

Virtual Reality (VR) provides immersive experiences that have fundamentally transformed the way humans interact with digital information. As VR becomes increasingly widespread, the demand for efficient text input methods continues to grow. Traditional text input techniques in VR, such as handheld controllers and hand gestures, become impractical when users’ hands are occupied or disabled. Although existing research has explored hands-free interaction alternatives like voice recognition and eye-gaze interaction, these methods are often hindered by issues such as ambient noise interference and calibration challenges. To address these limitations, we propose a novel hands-free text input technique based on foot interaction, addressing the shortcomings of existing approaches.

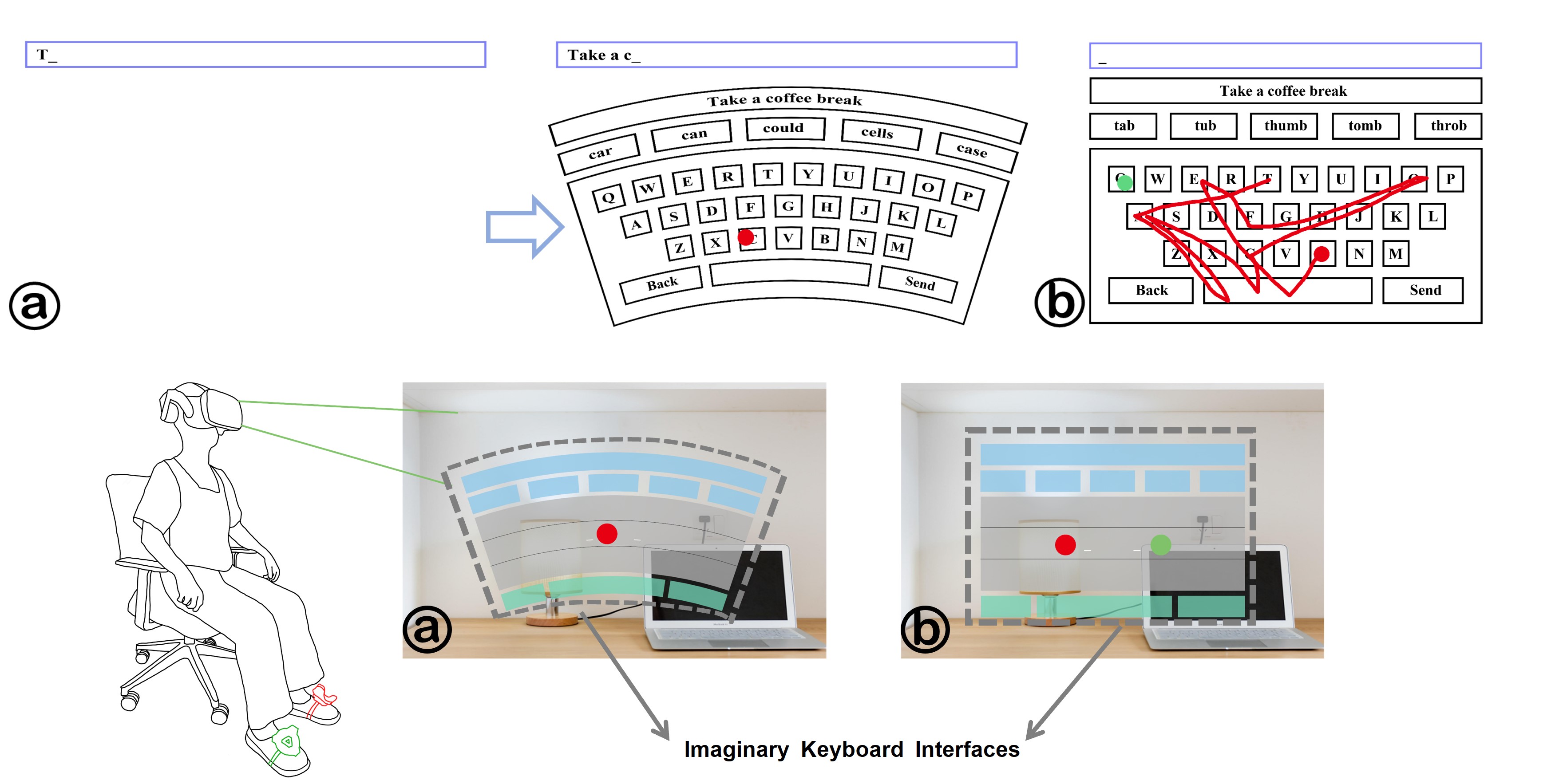

We first conducted a preliminary study to evaluate the feasibility of tap and swipe input approaches using foot-based interaction in both standing and sitting positions. Then three foot-based techniques(two tap-based methods and one swipe-based method)were developed to enhance the system’s performance and usability. We also designed an arched QWERTY keyboard with an ergonomic layout tailored to the natural movement trajectories of the feet and legs, thereby enhancing user comfort and usability of our system. These techniques were evaluated in a subsequent user study, revealing entry rates of 11.12 WPM and 10.80 WPM for the tap-based techniques, and 9.16 WPM for the swipe-based technique.

Design

Apparatus.

We used an HTC Vive Pro 2 for this experiment. It had a dual RGB low persistence LCD screen, a 2448 × 2448 pixels per eye resolution, and a 120Hz refresh rate. It was connected to a Windows 10 Pro PC with an Intel i9-11900 CPU and an Nvidia GeForce GTX 3090 GPU. The techniques and virtual environment were implemented using Unity3D (v2021.3.1f1) with SteamVR Unity plugin (version 2.7.3) and an HTC Vive Tracker 2.0. We chose a comparatively low-cost setup to ensure the wider applicability of our findings to devices available in the current market.

Typing Interface

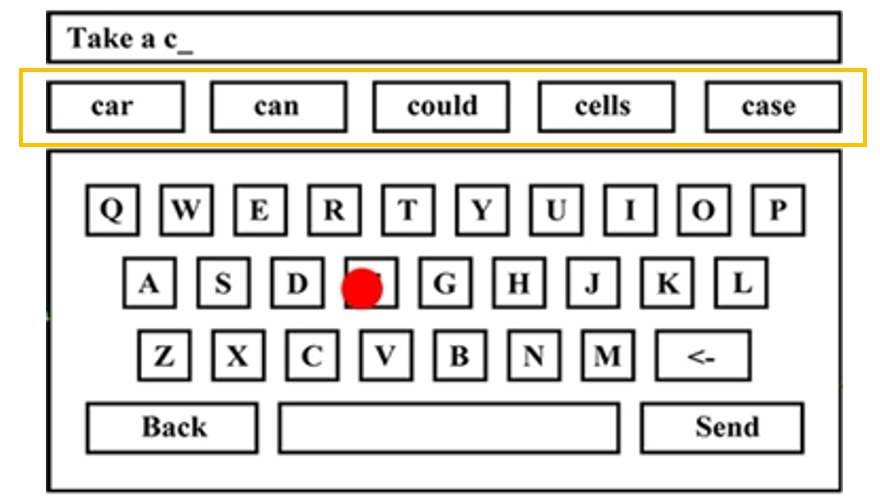

Users’ reluctance to learn new keyboard layouts, due to the challenges associated with adapting to different configurations, has contributed to the widespread adoption of the QWERTY keyboard layout in VR virtual keyboards. Therefore, we utilized the QWERTY layout to minimize learnability costs.

In the VR environment, we repositioned the keyboard interface from beneath the user’s feet to their direct line of sight. This modification aims to enhance user comfort and efficiency by eliminating the need for frequent head rotations to view a keyboard located under the feet. The interface within the VR Head-Mounted Display (HMD) consists of a text display area and a virtual keyboard. The text display area presents both the transcribed sentences and the text input entered by users.

The virtual keyboard has the following specifications:

- Position: 10 meters in front of users

- Dimensions: 3.6 meters by 1.4 meters

- Character Key Size: Uniformly sized at 0.3 meters by 0.3 meters

Experiment Design and Procedure

This study included two experiments, both employing within-subjects designs. In Study 1, the independent variables were Technique and Posture, resulting in four conditions. In Study 2, the independent variable was Technique, with three conditions. The order of conditions in both studies was counterbalanced using a Latin-Square approach to minimize order effects.

For both experiments, participants transcribed 12 sentences per condition, sourced from MacKenzie and Soukoreff’s phrase set. The first two sentences were designated for training and not analyzed, while the remaining ten were recorded for analysis. Participants completed a consent form, a demographic questionnaire, and an introduction to the tasks and VR setup. During each session, participants focused on speed and accuracy while seated in stationary chairs to avoid movement constraints. After each session, they completed post-task questionnaires, and semi-structured interviews were conducted at the end to gather feedback. Five-minute breaks were provided between sessions, and each experiment lasted approximately 60 minutes.

Methodology

Foot-based Interaction

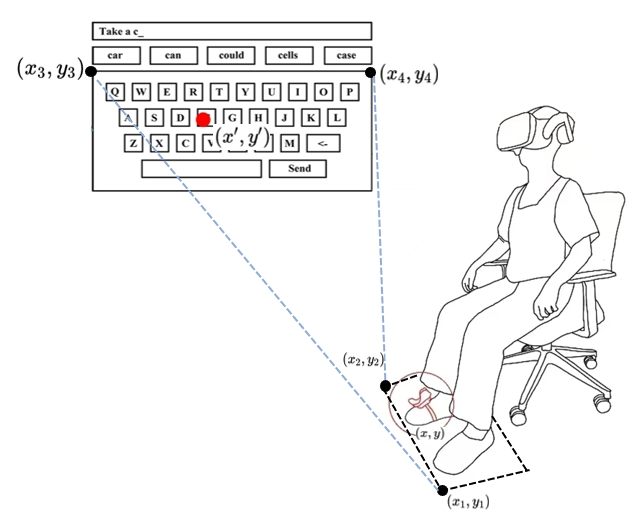

We implement interaction by tracking the position and orientation of the HTC Vive Tracker. The process involves the following steps: First, we map the user’s physical foot input area in the real world to a virtual keyboard in VR. The virtual keyboard is positioned 10 meters away from the user (i.e., $( z = -10 \, \text{m} )$), while the physical input area is on the ground plane. Therefore, the mapping is essentially a 2D coordinate transformation between two planes.

1. Length Mapping Before performing coordinate transformation, we account for the scale differences between the physical and virtual worlds. To ensure the physical foot input area matches the proportions of the virtual keyboard, we introduce a scaling factor $s$ to adjust the physical coordinates. Specifically, we take reference points $(x_1, y_1)$ and $(x_2, y_2)$ from the physical input area, as well as $(x_3, y_3)$ and $(x_4, y_4)$ from the virtual keyboard, and compute the scaling factor $s$ using the formula:

\[s = \frac{L_{\text{virtual}}}{L_{\text{real}}}\]where:

-

$L_{\text{real}} = \sqrt{(x_2 - x_1)^2 + (y_2 - y_1)^2}$

-

$L_{\text{virtual}} = \sqrt{(x_4 - x_3)^2 + (y_4 - y_3)^2}$

The scaling factor $s$ ensures that the physical input area is scaled proportionally to the virtual keyboard.

2. Rotation Angle Calculation To compute the rotation angle $\alpha$, we use the angle formula between the direction vectors of the physical input area and the virtual keyboard. Let the direction vector of the physical input area be $\mathbf{v}_1 = (x_2 - x_1, y_2 - y_1)$ and the virtual keyboard’s direction vector be $\mathbf{v}_2 = (x_4 - x_3, y_4 - y_3)$. The formulas for $\alpha$ are:

\[\cos(\alpha) = \frac{\mathbf{v}_1 \cdot \mathbf{v}_2}{\|\mathbf{v}_1\| \cdot \|\mathbf{v}_2\|}, \quad \sin(\alpha) = \frac{\mathbf{v}_1 \times \mathbf{v}_2}{\|\mathbf{v}_1\| \cdot \|\mathbf{v}_2\|}\]where:

- $\mathbf{v}_1 \cdot \mathbf{v}_2 = (x_2 - x_1)(x_4 - x_3) + (y_2 - y_1)(y_4 - y_3)$ is the dot product

- $\mathbf{v}_1 \times \mathbf{v}_2 = (x_2 - x_1)(y_4 - y_3) - (y_2 - y_1)(x_4 - x_3)$ is the cross product

3. Coordinate Transformation Next, we apply a combination of rotation and translation transformations to map the physical coordinates $(x, y)$ to the virtual space coordinates $(x’, y’)$. The transformation formulas are as follows:

\[x' = s \cdot \big[ (x - x_1) \cos(\alpha) - (y - y_1) \sin(\alpha) \big] + x_3\] \[y' = s \cdot \big[ (x - x_1) \sin(\alpha) + (y - y_1) \cos(\alpha) \big] + y_3\]where:

- $(x_1, y_1)$ is the origin of the physical input area,

- $(x_3, y_3)$ is the corresponding origin of the virtual keyboard,

- $\alpha$ is the rotation angle between the physical input area and the virtual keyboard.

For selection function, intentional toe tap is recognized when the upward lift of the toes exceeds 10 degrees. This threshold is intended to differentiate intentional toe tap for selection purposes from natural foot-tip elevations

For selection function, intentional toe tap is recognized when the upward lift of the toes exceeds 10 degrees. This threshold is intended to differentiate intentional toe tap for selection purposes from natural foot-tip elevations

Statistical Decoding Algorithm

The tapping-based text entry method handles the noise of input and predicts the input words with a statistical decoding algorithm.

The basic implementation is shown below:

The basic implementation is shown below:

1. Input Modeling

As the user enters each character, record the current input sequence $C$. Then, model $P(C|W)$ using the following formula:

- $c_i$: The observed character input by the user.

- $w_i$: The corresponding intended character in the word $W$.

To handle tapping errors and input noise, we used a Gaussian noise model.

2. Pruning

To reduce the complexity of word prediction, prune words from the lexicon whose initial letter does not match the initial letter of the input sequence $C$, i.e., For an observed input sequence starting with $c_1$, retain only words $W$ in the lexicon where the first letter $w_1$ satisfies $w_1 = c_1$.

3. Word Prediction: For each word $W$ in the pruned lexicon, calculate the posterior probability $P(W|C)$ using the following formula:

\[P(W|C) = \frac{P(C|W) \cdot P(W)}{\sum_{W'} P(C|W') \cdot P(W')}\]- $P(W)$: The prior probability of word $W$, derived from the frequency of the word in the lexicon. This lexicon consists of the 10,000 most probable words extracted from the American National Corpus (ANC). The probability $P(W)$ is calculated as:

Then select the top five words $W^*$ with the highest posterior probabilities and return them to the user interface (UI):

\[W^* = \arg\max_{W} P(C|W) \cdot P(W)\]- Return the top five candidates \(W_1^*, W_2^*, W_3^*, W_4^*, W_5^*\)

Word-Gesture Recognition

1. Lexicon Representation

1. Lexicon Representation

First, we converted each word in the lexicon (mentioned above) into a path. Each word is represented as a sequence of line segments connecting the center points of the corresponding letters on the virtual keyboard.

For example: The word “cat” is represented as a path connecting the centers of the letters “c”, “a”, and “t”.

This representation allows the algorithm to model the spatial structure of words for gesture-based decoding.

2. Input Preprocessing

After each commencement, we recorded the user’s gesture as a trajectory consisting of a series of points.

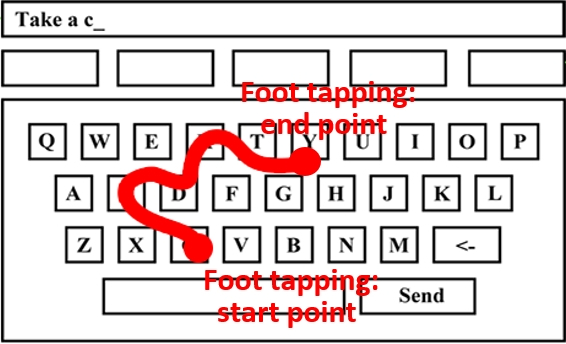

The trajectory input is controlled by the user’s foot tapping, which defines the two critical points: The start and end points as shown in figure.

Instead of using the raw points, these two points are processed and mapped to the center positions of the corresponding keys.

These mapped key centers are then used to prune the lexicon by filtering out words whose corresponding paths have start or end points that are too far away (e.g., more than one key-width) from the gesture’s trajectory, which decreased the complexity.

3. Gesture Path Matching For each candidate word, compute the similarity between the word’s path and the gesture trajectory:

-

The shape score is computed by calculating the pointwise distances between the sampled points of the gesture and the templates. To enable comparison, we first adjust the size of gestures and templates to be consistent (

L = 200). These distances are summed to produce the final shape score(the lower, the better). -

The location score is computed by calculating the pairwise Euclidean distances between the points of the gesture and the templates. A weighting factor (

alphas) is applied to emphasize the central points of the gesture.

Finally, we combine the shape and location scores into a single integration score

Results

Preliminary Study

Text Entry Performance

Text Entry Performance

-

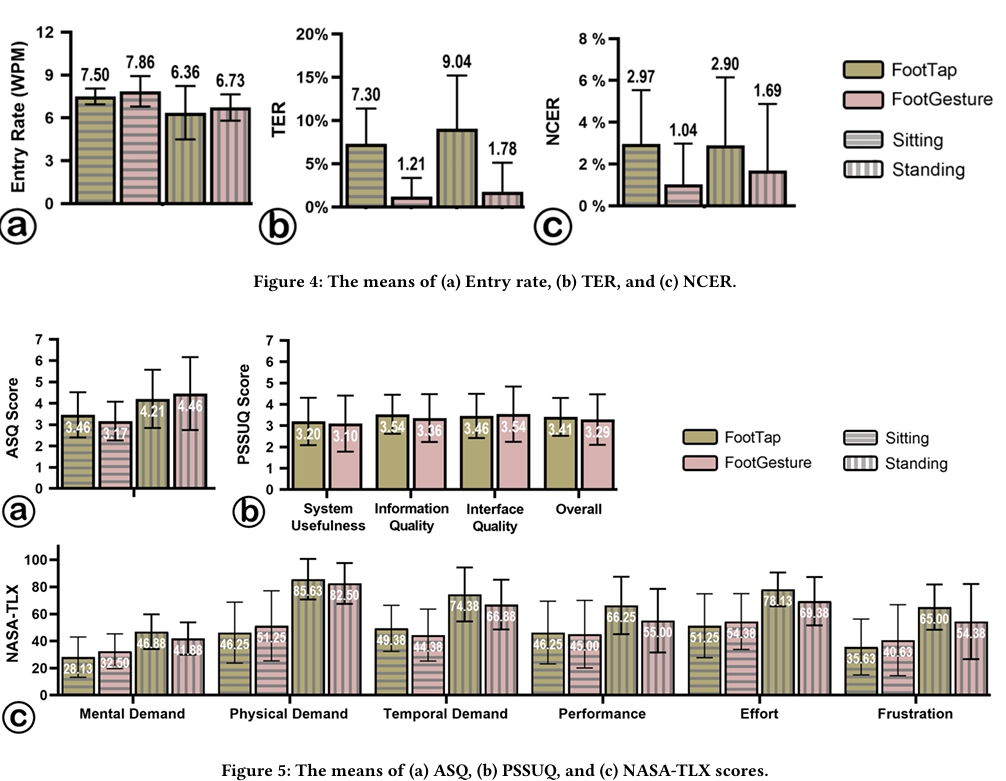

Entry Rate

- An RM-ANOVA showed a significant main effect of Posture on entry rate (𝐹₁,₇ = 9.292, 𝑝 = .019, 𝜂²ₚ = .670), with faster performance in the sitting posture.

- No significant effect of Technique on entry rate was found (𝑝 > .05).

-

Total Error Rates:

- Technique had a significant effect on TER (𝐹₁,₇ = 16.599, 𝑝 = .005, 𝜂²ₚ = .703), with FootGesture showing lower TER compared to FootTap.

- No significant differences were observed in NCER for Technique or Posture (𝑝 > .05).

Both FootTap and FootGesture achieved acceptable entry rates (over 7 WPM sitting, over 6 WPM standing) and low error rates (below 0.1%). However, entry rates were slower in the standing posture (6.73 WPM for FootTap, 6.67 WPM for FootGesture).

Usability and Perceived Workload

-

ASQ and PSSUQ Scores

- An RM-ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Posture on ASQ scores (𝐹₁,₇ = 5.060, 𝑝 = .050, 𝜂²ₚ = .445), with better usability ratings in the sitting posture.

- No significant differences in PSSUQ scores were found between FootTap and FootGesture (𝑝 > .05).

-

Workload (NASA-TLX)

- Posture had a significant impact on overall workload across all six dimensions of NASA-TLX (𝐹 = 246.524, 𝑝 = .004, 𝜂²ₚ = .999).

- RM-ANOVA analyses for individual dimensions showed significant effects of Posture on:

- Mental demand (𝐹₁,₇ = 5.948, 𝑝 = .045, 𝜂²ₚ = .459)

- Physical demand (𝐹₁,₇ = 73.085, 𝑝 < .001, 𝜂²ₚ = .913)

- Temporal demand (𝐹₁,₇ = 21.415, 𝑝 = .002, 𝜂²ₚ = .754)

- Effort (𝐹₁,₇ = 7.498, 𝑝 = .029, 𝜂²ₚ = .517)

- Frustration (𝐹₁,₇ = 11.641, 𝑝 = .011, 𝜂²ₚ = .624).

- Technique did not show any significant effects on workload.

ASQ and NASA-TLX scores indicate that participants preferred typing in the sitting posture, where physical demands and overall workload were lower.

Interview

- All participants (N=8) agreed that foot-based text input is feasible when hands are unavailable. They preferred using foot typing for lightweight tasks (e.g., sending messages), especially in a seated posture where no position adjustment is needed. For extensive typing, foot typing is less suitable for prolonged use but can serve as an alternate input method alongside hand typing, particularly when physical keyboards are unavailable. Foot-based typing is a promising alternative for communication when hands are occupied or head movement is restricted.

Study1

Entry Rate and Error Rate

Entry Rate and Error Rate

-

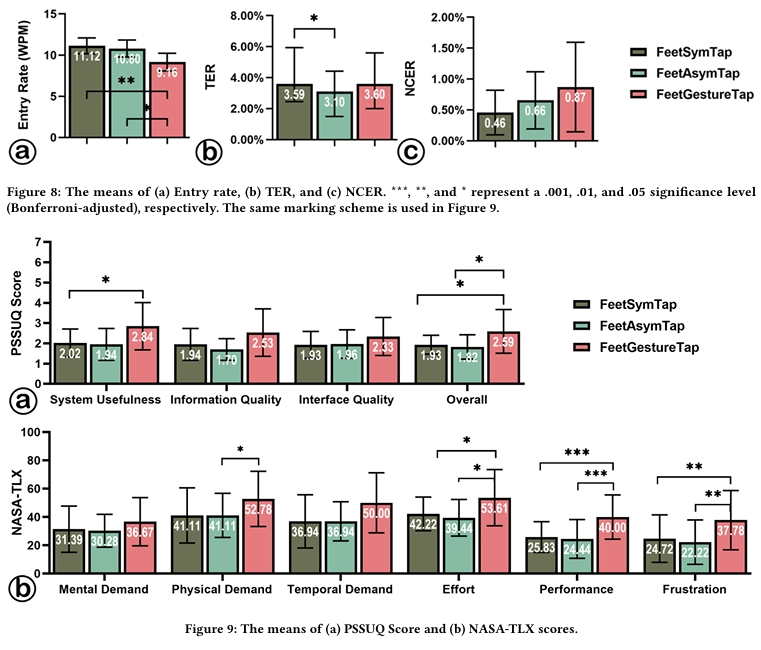

Entry Rate:

- RM-ANOVA showed a significant effect of Technique on entry rate (𝐹₂,₃₄ = 6.444, 𝑝 = .004, 𝜂²ₚ = .275).

- Post-hoc tests revealed that FeetGestureTap (𝑀 = 9.16, 𝑆𝐷 = 2.16) was significantly slower than both FeetSymTap (𝑀 = 11.12, 𝑆𝐷 = 1.94, 𝑝 = .006) and FeetAsymTap (𝑀 = 11.80, 𝑆𝐷 = 1.94, 𝑝 = .030).

-

Error Rates:

- Friedman tests indicated that Technique had a significant effect on TER (𝜒²₃ = 6.282, 𝑝 = .043, 𝜒 = .174), with FeetAsymTap (𝑀 = 3.10%) resulting in lower TER than FeetSymTap (𝑀 = 3.59%, 𝑝 = .020).

- No significant effect of Technique on NCER was observed (𝑝 > .05).

Usability (PSSUQ Scores)

- RM-ANOVA found significant differences in overall PSSUQ scores (𝐹₁.₂₆₂,₂₁.₄₅₄ = 6.454, 𝑝 = .014, 𝜂²ₚ = .275), system usefulness (𝐹₂,₃₄ = 5.127, 𝑝 = .011, 𝜂²ₚ = .232), and information quality (𝐹₁.₁₄₃,₁₉.₄₂₇ = 6.661, 𝑝 = .0115, 𝜂²ₚ = .282).

- Post-hoc tests showed:

- FeetGestureTap had higher overall scores (𝑀 = 2.59, 𝑆𝐷 = 1.17) than FeetSymTap (𝑀 = 1.93, 𝑆𝐷 = 0.45, 𝑝 = .041) and FeetAsymTap (𝑀 = 1.82, 𝑆𝐷 = 0.68, 𝑝 = .047).

- System usefulness of FeetGestureTap (𝑀 = 2.44, 𝑆𝐷 = 1.03) was rated higher than FeetSymTap (𝑀 = 2.02, 𝑆𝐷 = 0.66, 𝑝 = .029).

Perceived Workload (NASA-TLX)

- MANOVAs revealed significant differences in workload among techniques (𝐹 = 29.034, 𝑝 < .001, 𝜂²ₚ = .936).

-

RM-ANOVAs found significant effects of Technique on:

- Physical demand (𝐹₂,₃₄ = 3.570, 𝑝 = .039, 𝜂²ₚ = .174)

- Temporal demand (𝐹₂,₃₄ = 3.910, 𝑝 = .030, 𝜂²ₚ = .187)

- Effort (𝐹₂,₃₄ = 5.989, 𝑝 = .006, 𝜂²ₚ = .261)

- Performance (𝐹₂,₃₄ = 16.301, 𝑝 < .001, 𝜂²ₚ = .490)

- Frustration (𝐹₂,₃₄ = 12.840, 𝑝 = .001, 𝜂²ₚ = .430).

- Post-hoc Tests:

- FeetAsymTap (𝑀 = 41.11, 𝑆𝐷 = 15.58) required less physical demand than FeetGestureTap (𝑀 = 52.78, 𝑆𝐷 = 19.50, 𝑝 = .044).

- Participants rated their performance with FeetGestureTap (𝑀 = 40.00, 𝑆𝐷 = 15.62) lower than FeetAsymTap (𝑀 = 24.44, 𝑆𝐷 = 13.71, 𝑝 < .001) and FeetSymTapp (𝑀 = 25.83, 𝑆𝐷 = 10.88, 𝑝 < .001).

- FeetGestureTap (𝑀 = 53.61, 𝑆𝐷 = 19.84) required more effort than FeetAsymTap (𝑀 = 39.44, 𝑆𝐷 = 12.94, 𝑝 = .031) and FeetSymTap (𝑀 = 42.22, 𝑆𝐷 = 11.91, 𝑝 = .032).

- FeetGestureTap (𝑀 = 37.78, 𝑆𝐷 = 20.95) caused greater frustration than FeetAsymTap (𝑀 = 22.22, 𝑆𝐷 = 10.65, 𝑝 = .001) and FeetSymTap (𝑀 = 24.72, 𝑆𝐷 = 15.95, 𝑝 = .003).